Portable

Amateur Radio History,

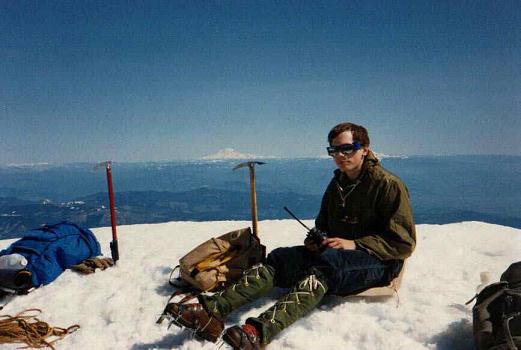

W7ZOI / 7

W7ZOI/7, Field Day

with KD7LXL, 2002, Near Naches Peak,

Wes Hayward,

w7zoi.

Updates:

4Jan11, 14Jan11, 15April11, 24April11,

27June11, 25June12, 15aug12, 24June13, 28April16,

3July16, 13Aug16, 21Dec16, 28July18, 6May2019

,29june2019, 20Dec2020, 3Nov2021

Click here for reports for Field Day

2011, Field

Day 2013, Field

Day 2016 , UHF

Contest--August2016, Field

Day 2018,

Microwave-Sprint, May

2019, Field

Day 2019, FYBO 2007,

ARRL

September VHF Contest 2002 on Maxwell Butte

All Photos on this website are my own. I took

them, or they were taken by my sons or other

hiking/climbing companions. I've tried to

acknowledge the photographer. None

of these photos are the result of web surfing.

All photos are

copyrighted: If you want to use a photo on

your own site, just write to me about

it. {w7zoi}{at}{arrl dot net}.

Introduction

This web thread deals with portable amateur radio

activities where equipment is taken into the

field. Amateur radio has sometimes

been the main reason for the outing, such as

participation in a contest. Just as often,

the ham gear has been taken along as a supplement

to a hike, a climb, or a backpacking junket.

Some folks also carry their ham gear along

on trips with bicycles, canoes, or kayaks.

All fall into the realm of this discussion.

This site is strictly a personal history of some

of the things I have done and does not deal with

the activity of others in this area.

While many of the photos show operation with

friends and/or relatives, this is not a site for a

specific club or group. All of my trips

have been on foot in the mountains of the US West.

There are other sites on the

Internet that specifically deal with portable

operations and I encourage the interested reader

to investigate them. An especially

good one is SOTA, or "Summits on the Air."

This organization was founded by Richard, G3CWI

and his colleague, G3WGV. Click HERE to

get to the

There is a down side to the SOTA activity:

It tends to emphasize operation from named,

documented summits. There are many parts of

this country where summits of any kind are rare,

yet there is more than abundant opportunity for

portable ham operations, perhaps coupled with

kayak or canoe boating on water. Land

travel may be by foot or bicycle.

Even when in the mountains, it is not

necessary to be on a summit to garner the thrills

and advantages of portable operation.

Often an un-named ridge or pass will provide

views and antenna opportunities that rival those

afforded the summit traveler. I generally

just look for good radio locations (that must also

be scenic) and do not worry about them being a

summit. Alas, by now most of my peak bagging

days are past anyway.

The dominant reason for taking ham gear into the

field is very simple; it is great fun.

But there is serendipity: It is

always good to exercise our skills to be ready for

an emergency. Amateur radio can be

effective in moderately remote mountain locations

where nothing else is available, other than some

expensive satellite services.

There are two additional factors that motivate us

toward portable operation. The first

is the restriction often imposed upon us by our

lifestyle within society. Many folks

live in apartments in cities where antennas are

nearly impossible. (Some folks manage to

get on the air with attic antennas and the like,

but it requires imagination and sometimes a lot of

work!) Others live in developed housing

areas where antennas are discouraged, if not

strictly prohibited. Portable

operation may be the ideal solution for the folks

fighting these restrictions.

The other factor is noise. This is one that

I'm presently fighting, albeit only with marginal

success. The noise comes from the

many electronic gadgets that are said to enhance

our lives. It's hard to find a

household that doesn't have numerous computers

running. This goes beyond personal

computers to include the microprocessors in the

microwave oven and the clothes washer. It

also includes the insidious digital data

converters that supply us with high speed

internet, telephone, and high definition cable

television services. Light dimmers

and touch lamps are other problems.

The noise emanating from these sources is

relatively short range. Some of it can

easily be attenuated merely by walking away from

it. I'm amazed how quiet a band can

become when I walk a mere quarter of a mile into

the woods south of my neighborhood.

Some noise sources are stronger and propagate further.

These can be heard in the local parks, but

completely vanish in the mountains.

It is sometimes quiet on the ocean beaches of the

West, but not always, for they are often close to

civilization.

There is a more esoteric, yet equally important

virtue to portable operation -- it provides an

activity in our lives that instills a sense of

adventure. We need this. Even

as a "geezer," I still yearn for the excitement

that was more common in my youth.

Rock climbing and mountaineering are, alas, little

more than memories for me. But I still

manage to get out for some hiking, modest

backpacking, and even some casual winter snow

shoeing. Portable ham radio is often

part of these junkets. The

radio contacts from the field, even to just the

next state, can be more exciting than the best DX

garnered from home!

OK, so much for the preface -- let's get to the

subject. Some of the things to be discussed

are HF contesting from the hills, including Field

Day, VHF contests, winter operations, and special

events including an interesting, albeit obscure

winter QRP version of "field day". But the

discussion starts with personal history.

First treks

By the time I started

participating in amateur radio (Novice license in

1955) I had already done a little bit of

backpacking, starting with Boy Scouts. Both

interests grew more or less together and it was

reasonable that at one point they would merge.

Both activities continue with me, over a half a

century after they began. My first hike with

radio gear was in July of 1958 with my brother

Den. We hiked to the top of

I had made a sked

(schedule) with George, K7BFI ahead of time,

not knowing if we had a chance of working anyone

else. The transmitter ran about a half watt input

power to a single 3S4 tube powered by a 90

volt "B" Battery while the receiver was a three

transistor regenerative job (see QST, July, 1957,

p36.) My only photos of that trip did not

show the rig or the operation. The rig

itself is also long gone, but I hope to duplicate

it someday. I vividly remember just

how strong George's signals were from the hilltop.

I also recall hearing some weak signals in

the background that I would never have heard from

home. I worked George on both 80 and

40 meters. Noise was absent to a level that

I had never experienced. The same rig was

included on a mountain backpacking/fishing trek

later that summer, but nothing was worked or even

heard. But we had camped at a lake deep in

the woods, surrounded by mountains, so it is not

surprising that nothing was worked.

WA6UVR/6. (1961-1966)

I finished my undergraduate college experience and

got married in 1961 and we left the northwest for

The photo above shows the first time I combined

amateur radio with an overnight backpack and

climb. This was Field Day of 1965. I

was joined by Chuck Wilcox, K6DMW, on a hike up

the north ridge of

This was the rig on

This is the north face of

Again W7ZOI / 7

(photo by Andre' Zoutte, WA7IHJ.)

I'm operating at the left. One fellow was holding

the antenna mast while another steadied the call

pennant in the wind for the photo. Note the

RG58 coax blown out by the wind. While the

temperature was blistering hot over most of the

So what's this

The late 1960s and early 1970s

era included a great deal of experimentation, much

of it related to rigs for the mountains.

Some early direct conversion receivers

resulted from some of this work.

Urges to build portable rigs happened a couple of times

per year. The

"spring" motivation is predictable. But it also

seemed to happen in late fall and early winter

when

Both boxes run an output of about half a watt, a

level that we concluded was about right for an

extended trip (batteries that one can carry) while

still offering reasonable performance. Modern

batteries (year

1990 and on) will easily support higher output

power. Both rigs saw considerable

application in the mountains with the right hand

photo showing the Micro mountaineer in use, Dec

1972. Operation with gloves or

mittens is a must. Both units provided

technical direction for equipment to

follow. The photo of me

operating in the woods was taken by Gene Single,

K7IUN. Incidentally, that photo

was not posed. I was actually working

VE6WG when the photo was snapped.

Commercial equipment continues to

evolve. Consider the photo

below:

(N7FKI photo)

(N7FKI photo)

This photo

shows a recently introduced, ultra compact and

versatile "trail friendly" commercial transceiver,

the KX2 from Elecraft. (photo taken in June,

2016). This KX2 belongs to

N7FKI. (I eventually bought one too.)

This little box is just slightly larger

than the Micromountaineer

above, weighs just over one pound with battery, offers CW and SSB

plus digital modes, and delivers up to 10 watts.

It's truly amazing how far things

have come.

ARRL Field Day

The ARRL Field Day was often a major activity in

my schedule of Mountain/Ham treks.

These were often collaborative efforts.

Considerable effort was sometimes devoted

to building rigs and antennas especially for FD,

and in the development of some ancillary tools.

The following photo shows a table that

could be dismantled and stowed in a pack.

W7EL/7,

late 1970 time frame. The lower

shelf houses a transmatch and rather heavy battery

while a couple of transceivers and a keyer are on top.

One of the transceivers is one that

was described in Solid-State Design for the Radio

Amateur, p214. (ARRL, 1977) Two clip

boards were used for this operation. One is

for the log while the other is a cross-check

sheet. (By now, we were making enough

contacts that this was necessary.) A half

amp solar panel was included in the mix, although

we later discovered that ARRL ruled it illegal,

for we were using the panel to top off the

storage battery. They wanted solar

contacts to occur without a storage cell. We

had done that often, but not always when in the

field. Oh well.

We were picking up some other lore along the way.

For example, it was vital to include

mosquito nets and/or repellent. But some of

the most effective brands of "bug juice" have the

nasty chemical property that they react with the

classic yellow paint on pencils. So,

we often kept our pencils wrapped in plastic.

Another

detail

that we observed was the difficulty in

getting lines into the high trees that we often

encountered. We eventually started taking a

sling shot and a spinning reel with medium weight

fishing line. This tool allowed us to get

the antennas up to quite high levels. The

limitation now became the weight of transmission

line that we were willing to pack in. This

photo shows

Another

detail

that we observed was the difficulty in

getting lines into the high trees that we often

encountered. We eventually started taking a

sling shot and a spinning reel with medium weight

fishing line. This tool allowed us to get

the antennas up to quite high levels. The

limitation now became the weight of transmission

line that we were willing to pack in. This

photo shows

By 1989 son Roger

(KA7EXM) had graduated from college and was living

in

This

view shows

Here's Rog, just

after we reached the top. The peaks on the horizon

to the north are around

This is the 40M rig used on McLoughlin,

a direct conversion transceiver running about half

a watt output. The transceiver has a

couple of crystals built into it, but also has a

VFO that can be used. The VFO is the box

riding "piggyback" on the transceiver. The

smaller box is a transmatch. The red

enclosure houses C sized NiCad batteries.

Our "table" was rock at the top of the peak.

The right photo shows a stuff bag housing

the entire station. The collapsed antenna

mast is 14 inches long, but expands to 12 feet; it

supported an inverted Vee

fed with RG-174 coax. This is the same

support used on Adams and Dana. Many thanks

again to Chuck, K6DMW, for that 1965 contribution;

it has certainly been used a lot!

The left photo above shows the 40 M rig with

This

was our high camp on top of McLoughlin.

We used bivouac bags instead of a tent.

One

can see some unusual things when camped on top of

a peak. Here we see the shadow of our peak

at sunset.

McLoughlin was an

excellent radio location offering a comfortable,

single propagation hop on 40 M to much of the US

West Coast. With only half a watt output,

we still made a pile of contacts.

While we tend to think of the summit of a peak or

pass as being the ideal location, that is not

always true. On one trip, Roger and I ended

up in a stand of trees well below the pass that

had originally been picked from studies of the

maps. The pass just looked too hostile as a

camp place, especially in the rainy weather we

were experiencing.

The pass is at the right edge of the left photo

above while our eventual camp is shown on the

right. This shot shows me (well, my boots)

operating in light rain. This location

turned out to be especially good, for the slope

behind and below provided a lower angle launch to

the east than we would have obtained from the

pass. (Roger and I crossed that pass a few

years later.) See the now classic

book by Moxon for a

discussion of dipoles that are below the summit.

(L.A.Moxon,

G6XN, "HF Antennas for All Locations,"

RSGB, 1982.) That location

would be a good one for a return trip. Hmmmm.... Roger?

Note that we were camping on snow. This is

a common situation for FD, which happens early in

the summer backpacking season. Snow

normally presents no problems so long as some

insulating pads are included for sleeping and

operating.

Through the 1970s I often did FD with Jeff,

WA7MLH. Sometimes we cheated and operated for a

few hours from a location that was close to the

car, although it always made us feel guilty. On

other trips we went to the south side of

WA7MLH

The gear shown above is a pair of CW transceivers

for 40 and 20 M that I used. Jeff had taken

rigs along for DSB. He has amassed a great

deal of back country experience with SSB and DSB

at powers from less than a watt up to about 30

watts. Click HERE

to see Jeff's most excellent web site

about his appliance-free shack.

Some of the Field Day trips outlined above take on

mini-expedition characteristics with a lot of

planning and a lot of junk to pack into the hills.

FD can equally be a casual event

where a minimal rig is thrown into a rucksack and

taken out for the day. A FD of this type

was to

The left photo shows Rick listening to my

transceiver while the right shot shows the rig and

log book.

This is a

1996 Field Day shot of yours truly making a few

final contacts before the antenna was taken down

and we hiked out. The weather had

been good, but it was starting to rain lightly by

the time this photo was taken. This was the

last contact before the log book and the gear was

shoved into the pack for the hike out.

(KK7B

Photo.)

The photo above features my grandson, Tom, KD7LXL,

digging into his pack to find a rig to go with the

antennas we just erected. This was on FD of

2002. The lead photo at the top of this

page is also from that 2002 trip near

Field Day with Single

Sideband

I'll admit to being a hopeless CW enthusiast.

Like most of the kid hams I

encountered when I was in high school, I got my novice

license with the thought, "Well, I'll learn the

code to get my General and then I'll get on

phone." But like many of us, I got hooked

on the excitement of CW, especially when I

discovered how much more I could do with simple CW

gear compared to simple phone gear. Times change.

I'll admit that I've had a lot of fun

building SSB gear. It's been fun to design

it, get it going, measure it, and put it on the

air. But I still don't enjoy SSB operation

as much as I do CW, even today.

I've operated SSB with low power during Field Day

on a few occasions and it has been a lot of fun.

Shown below is a 1997 operation at a park

about a 10 minute hike south of home.

This transceiver operated on the 40 meter band

with an output of about 1.5 W on both SSB and CW.

While this may seem like an excessively low

power for phone operation, it was still quite easy

to make contacts on Sunday morning of Field Day

weekend. The SSB transmitter included

speech processing in the IF. Although the

SSB experience was fun and successful, it was even

easier to make CW contacts with the same antenna

and power output. Often the CW

contacts were much further away than those I did

with SSB. At home, this rig was

used with an outboard 20 W power amplifier that

greatly enhanced the results.

See Experimental Methods in RF Design

(EMRFD, ARRL, 2003) and QST December, 1989 and

January, 1990.

The above shot shows an unusual SSB station, this

one for the 20 meter band. This was the

brainchild of a good friend, Bob Culter, N7FKI. Bob

has an Elecraft KX-1 multiband CW transceiver.

One of the bands is 20 meters. Bob

realized that the internal menus would allow

considerable latitude in offsetting the nominal

carrier frequency from that received. With

this freedom, it was possible to use the

transceiver in the receive mode to copy SSB, but

to then use the transmitted carrier as injection

for a phasing transmitter. Bob based

the transmitter on KK7B designs, but with RF

circuits redesigned for the 20 meter band.

He then built a linear chain ending in a

Mitsubishi RD16HHF1 MOSFET running about 8 watts

output power. The speech processor in Bob's

rig used an Analog Devices SSM2167 integrated

circuit. The rig was much more effective with the

speech processor in operation. This Field

Day operation occurred on the playground of an

elementary school close to Bob's house.

Tom, KD7LXL, and I used some SSB on 15 M with his

Yaesu FT-817 during FD

for 2002. That was close to a maximum

in the sunspots and conditions were

outstanding. We worked quite a few folks

around the US while using nothing more than the 5

watt transmitter output with a 40 meter dipole

about 10 feet above the snow. See the lead

photo for this web article.

Other Seasons

Field Day is always fun, but amateur radio in the

back country is certainly not restricted to that

one weekend. Often, Field Day weekend is

too early in the season to get to the interesting

locations in the western states, for the roads are

still snowed in. This varies, year to year.

Later in the summer is usually more

practical, but does not fit with the amateur radio

calendar. In addition, the trips

later in the summer are often reserved for more

intense backpacking efforts and may not include

ham gear. This leaves the most of the

rest of the year for ham treks. Spring and

autumn are both good. Some of the best

radio trips I've done have been in winter.

The earliest of these was a snowshoe trip to

Here's a photo looking into the entrance of an

abbreviated snow cave that I dug on a mid 1980s

solo trip. The transceiver is sitting on "the

roof," right after keeping a sked

with WA7MLH. It was a kick to work Jeff from the

field after I had worked him so often from home

with him in the hills. Setting radio aside,

the mountains are a special place in wintertime

with an intense quiet that becomes hard to imagine

after the busy, crowded world we normally

experience. A quiet radio environment adds

to the enjoyment. The contacts are

also fun and often unusual. Imagine an early

dinner, followed by retirement to the warmth of a

down sleeping bag with the transceiver and

batteries pulled inside where the wonder of it all

is described in the language of CW to the folks

who are still at home.

This shot shows another quasi-snowcave.

Even without a roof, the shelter

trench offers a warm place to relax and protection

from the wind. Roger and I dug this

one while on a day trek on snowshoes. The

goal for that trip was to exercise a new rig in

the field. The rig was an updated version

of the Micro mountaineer, later presented in QST,

July, 2000. The trip was in February,

2000. The larger item on the cave shelf was

a stove to make soup for lunch. It's

amazing how much warmth is provided by a shelter

like this that is dug in only 10 or 20 minutes.

Here's another shot of

VHF Portable

Among the great virtues of being in the mountains

is the great panorama presented. The

most obvious vista is the visual one, but the mountains also

provide an extended radio vista, one that is

especially useful at VHF. It's a

thrill to operate from a slightly rare grid square

that is a long distance from population centers

and to generate pile ups on the VHF bands.

Over the last dozen or so years I've had

the pleasure of going on several expeditions with

son Roger, KA7EXM. He has managed to put

several interesting grid squares on the air and to

make some very interesting, relatively long haul

VHF contacts. The modes that he has used

are CW and SSB, all with QRP power levels.

We always use his call on the VHF

expeditions.

(Photo by either KA7EXM or WB6JZY.

TNX guys.)

Roger and his work colleague Jack Trollman, WB6JZY, near the

summit of

Roger's VHF antennas are generally Yagis for 2M and up.

A simple dipole is used for 6M. The

6M activity is not usually featured, but is

sometimes included merely because his main

transceiver, an

FT-817, includes that band. The VHF Yagis are those described

by WA5VJB. See the articles in CQ VHF,

August 1998 and October,

1998. Roger has built these antennas

for 144, 222, and 432 MHz with excellent results.

He uses a homebrew transverter

for 222 MHz. See the article in QST by

W1GHZ, January, 2003.

The above two photos show Roger working folks back

in

This

photo of Roger is from another VHF SS trip to the

same general area on the Pacific Crest Trail.

Roger on the summit of

Roger keeps an on-line list of his VHF portable

activity. Click HERE

for that list.

Here are a couple of shots of Roger on a trip we

took to "tie in rock" above the Elliot Glacier on

One of the best VHF mountain

topping treks we did was to Maxwell Butte in the

Mt. Jefferson Wilderness Area of Oregon.

Here's Roger working a few guys on 144 MHz CW.

For more info and more photos on this trip,

click here.

The ARRL approach to VHF contesting

differs from that used for Field Day. The

FD rules include a "Class B" where one or

two people can operate a single

transmitter station. This class adapts

itself well to backpack contesting efforts.

In contrast, the VHF contest rules have a QRP

class, but restrict it to a single operator.

Because of this, I have rarely participated

in any actual station operation on our VHF

junkets. There have been moments

where I would love to have operated a little, but

it is a "single operator" event. Oh

well. One approach is to go into the

field, work the contest, but to never submit a log

or score. Rules don't really matter

then. The down side of this is that the

published results are not then representative of

the actual activity. Even this is of little

consequence owing to data-mining that happens with

submitted logs.

All of our efforts have been with SSB and CW.

These modes are clearly preferred for long

distance weak signal applications. FM can

still be effective if the location is good enough.

FM is also a very useful tool for

communications within a group that may be spread

out on a trail.

An outstanding location for any mode is the summit

of

UHF Portable

Our main emphasis has

been simple HF CW operations. However,

son Roger has become quite interested in portable

operation with VHF gear. His

experience has taken him up through 432

MHz. (Cell phones don't

count!) We recently joined John,

K7CVU, on a hike to a location that we have

visited in the past. But this time we

took UHF gear. John had a transverter that ran 2.5

watts output at 1296 MHz. His

antenna was a 5 element Yagi

that we put atop a small backpacking camera

tripod. The IF for the transverter

was a Yaesu

FT-817.

Here

we see K7CVU in 2008 with his 5 element 1296 MHz Yagi. This

provided contacts as far away as 168 miles.

I suspect that we will try to do more

at UHF, for this was extremely fun.

Click here

to read about this trek.

Update: We did another UHF mountain top

trek, this time in May, 2019. The location

was the Coast Range of Oregon. John

added 2304 MHz this round. Click here to

read about that one.

Here

we see K7CVU in 2008 with his 5 element 1296 MHz Yagi. This

provided contacts as far away as 168 miles.

I suspect that we will try to do more

at UHF, for this was extremely fun.

Click here

to read about this trek.

Update: We did another UHF mountain top

trek, this time in May, 2019. The location

was the Coast Range of Oregon. John

added 2304 MHz this round. Click here to

read about that one.

Equipment Thoughts

Often folks will ask about rigs for portable

operation. There are many choices

these days including a number of high performance

kits. I still prefer to brew my own.

The experience is then more complete with the

operation becoming an extension of the experiments

that led to the gear.

I presently have several 40 M CW rigs that I take

to the mountains. One is a VFO

controlled superhet shown below.

This transceiver runs 1 watt output and has

several features built into it including a

frequency counter and keyer.

The string of Ni-MH batteries

shown will power the rig for a typical

weekend of operating, if not longer. (The

heavy keyer paddle

shown is only used at home!)

The front panel LED ceases to function if

the battery voltage drops below 11.5. The

transceiver weighs just over 1 pound with a

receiver current consumption of about 35 mA.

Click HERE

to see the schematic for this rig.

Similar gear for the 14 MHz band features improved

performance with more power and a stronger (higher

dynamic range) receiver front end. This equipment

is described in Experimental Methods in RF

Design ( EMRFD,

ARRL, 2003).

Commercial gear for the VHF bands is readily

available although it is not as common as that for

HF. One popular offering is the Yaesu FT-817. The

performance has been completely satisfactory, with

one major exception: The FT-817 eats

batteries alive. On the mountain top

contest activities, we have often carried an 8

Amp-Hour Sealed Lead Acid battery to run the

FT-817. Starting with a full charge, it is

depleted by the end of an overnight contest.

The problem is not high transmit power.

Rather, it is the excessive current consumed at

all times. This results from the use of

relays for all band switching. The

FT-817 is a good choice if the operating interval

is short.

A much older monoband

rig offers performance that is, in many ways far

superior to the later multiband designs.

This example is a classic 2 M SSB/CW rig, the

IC-202 from Icom.

While the rig itself weighs more and is

larger than the FT-817, the total weight per watt

is much less when batteries are included.

Receive current for the IC-202 is around 70

mA, so it will last

for an entire contest with a set of internal

C-cells. We have also had good luck with a

Mizuho MX-2. This little rig produces a

couple of hundred mW

of SSB and CW output in a package the size of a

traditional 1980s era FM hand held.

The Mizuho uses a convenient 9 volt supply.

One portable rig from

Elecraft, the KX3, is also

noteworthy. This box provides CW

and SSB on all HF bands plus 6 Meters.

A 2 Meter internal transmatch is an

option. This box is quite light

weight and has low current consumption and would

be an option. A cousin to the

KX3 has just (2016) been introduced, the KX2, and

it is even smaller and lighter.

However, it covers fewer bands.

There is clearly justification for brewing one's

own rig for the VHF bands. Numerous

examples are included in Experimental

Methods in RF Design (EMRFD, ARRL,

2003) to serve as a starting point.

Several variations of a phasing transceiver

for 2M are shown in Chapter 12. A

Universal Monoband

Superhet Transceiver is presented

in Chapter 6 (see page 6.83) with

the one shown operating in the 6M band. It

could be built for any HF band or even for 2M

merely by changing some LC filters and the LO

chain. That rig has been a great

performer, yielding sporadic E contacts from W1 to

Homebrewing will

become necessary as we move to

UHF. Some commercial FM gear is

available for 1296, and imported SSB/CW transverters are

available. But there is no turn-key

solution available. Perhaps this

is part of the lure of the 1296 MHz band?

How Heavy is the Pack?

This photo shows a vital part of the game, that of

at-home testing before taking the gear into the

field. In this case, the total weight of

the station is determined with a kitchen scale.

It's coming in at about 2 pounds, or

a kilogram for the set up shown. Note that

the keyer paddle,

earphones, and battery are included with the

transceiver. The antenna system must also

be included when planning for portable outings,

for that is part of the pack load. After

the "weigh-in," the equipment should be set up and

used, taking care to add nothing more than the

gear that was on the scale. There is

an old adage for backpacking that says "Worry

about the ounces and the pounds will take care of

themselves." This clearly applies to the

radio gear that will be carried into the field.

It is very important to use the gear at home just

as it will be used in the field. If a

commercial rig is to be used, try to set the menu

items at home so that frustrations are avoided

once on the hill. This is, of course,

not a problem with homebrew gear used by the

builder, for he or she will know how the menus

function!

Some popular antenna solutions can be excessively

heavy. The telescoping 12 foot antenna mast

that I've used for many years weighs about 2

pounds. It easily fits in a pack and is

very robust, so it has been a reasonable solution

when traveling above timberline where there are no

trees. A better solution is a modern

fiberglass crappie type fishing pole that expands

to a 20 ft length. It weighs only one pound.

It is the preferred solution and is popular

with many QRP radio amateurs taking gear into the

field, although it does have the disadvantage that

it is still long when collapsed.

The one I have is 45 inches, so it won't fit

inside a pack. It is easily strapped to the

side of one though. A wonderful telescoping

mast is available that expands to 33 ft, or 10 M

length. It's a great thing if one is going

to do an automobile bound portable stint.

But that mast weight is 3.5 pounds, making it of

marginal utility for most backpacking.

These pack weight comments are predominantly

"geezer" considerations and should not be regarded

as limitations by younger hams or those used to

hauling heavy packs. We hauled large

loads in our youth and a few extra pounds in the

pack made little difference then. But times change.

Most of us tend to be more concerned

about pack weight as we add a few years to the

tally.

Final Thoughts

Finally, a word of

caution: The activities presented

here are avocations that we have, by now, pursued

for over 60 years. They are not extreme and

certainly do not compare with the feats of the

modern 21st century backpacker or mountaineer.

They can still be more demanding than

a trip to the back yard or local

park. If these activities are new

to you, by all means go with someone who has done

them before. Always take the right

equipment and know how to use it before you arrive

in the woods. Beware of some of the casual,

small packs that are sold to the QRP community.

These are sometimes found at hamfests or ham-equipment

stores. Some of these packs have no room

for anything other than the intended rig.

Know about the backpacking "Ten Essentials"

and always carry them with you when in the back

country. (Ref: Mountaineering:

The Freedom of the Hills,

Seattle Mountaineers, 1st

Edition published in 1960. The 7th or 8th

edition is in print at this time and is still a

great book.)

With that said, give some portable operation a

try. Even if it is just to a local park, it

can still be quite exciting and great fun.

Indeed, it may be the most fun that you will

ever have in amateur radio. That's been the

case with me.