W7ZOI Field Day for 2013

(posted 24June13, Wes Hayward)

The ARRL Field Day is the premier annual amateur radio operating

event for many of us. Occurring on the fourth weekend of June each

year, it is the time

when radio amateurs from the US and Canada go into the field,

often camping,

taking their radio gear with them. Essentially an

excuse to go

out into the wild with portable radio gear to just have a lot of

fun, Field

Day is also an exercise in emergency preparedness.

Most of the

amateur radio community operates from locations that are next to

the road,

often from the comforts of lawn chairs with picnic tables, usually

with large

gasoline powered generators chugging away in the

background. There is a small but growing

faction that integrates FD with a walk into the

hills.

I remember going to the FD site for my old local club when I was

in high school in the late 1950s. The guys in our club

were out for blood with a devoted contest mind set, so the kids

never got a chance to operate. In the early

1960s, when I was beginning to build and experiment with solid

state gear, I started going on FD with battery powered

rigs. Some

of those outings were with friends where we operated next to a

road. The more interesting and fun trips have always

been from the trail.

This year I really wanted to get out for a backpacking

operation. I'm still able to do this and want to take

advantage of it while I still can.

I was lucky to find a willing partner for the trek in John

McCormick, K7CVU.

John, another ex Tektronix guy, has extensive mountaineering

experience in

the American West including Alaska, plus some climbing in

Europe.

Our goal was to pick a site that had a scenic view, was a

reasonable radio

location, and was accessible by trail, perhaps with some modest

cross country

travel. After checking with other local folks who do

this sort

of FD, we found that Ghost Ridge wasn't to be occupied, so we

headed there.

I've been there often and it's a favorite location for day trips

in all seasons.

John had been there on skis in winter.

Ghost Ridge is a name applied by local Nordic ski enthusiasts to

an area south of historic Barlow Pass, an early route across the

Cascade Mountains connecting Oregon's Willamette Valley with the

rest of the Oregon Trail. The Ghost name makes

reference to pioneer graves in the area, attesting to the rigors

of the journey a century and a half ago. Barlow Pass

is accessed from Oregon Highway 35. From a trailhead at the

pass, one hikes south on the Pacific Crest Trail

(PCT.) After just over a mile, the route leaves the

trail to follow the ridge line to the summit of Ghost Ridge at

Peak 4925.

My normal comment, when writing a report of this sort, might be

that the trail hike was casual and uneventful. This

was not the case this year. The trail hike

provided an extremely enjoyable, unique experience that I’ll long

remember. I’ll return to

this later.

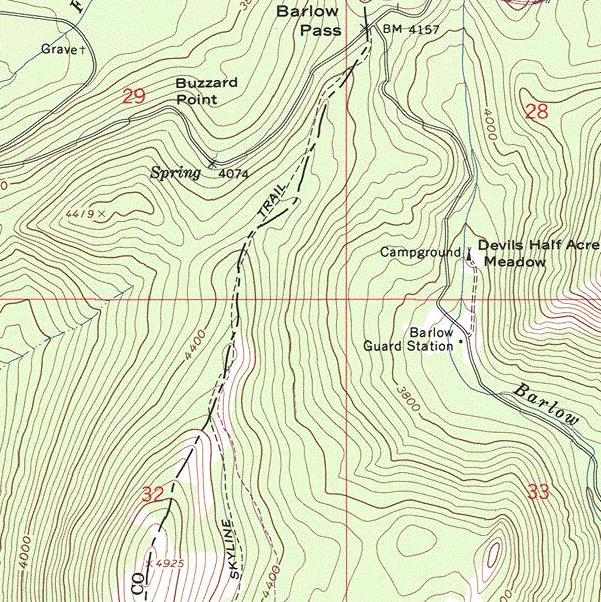

Our route is shown in the map below. The Barlow road,

now little more than a jeep path, is presently

closed. The PCT is call the Skyline Trail

on this older map, although that name is no longer used.

We left the trail at the point where the Skyline Trail peaks and

descends slightly. We now found ourselves in timber

with sparse brush. Following the obvious ridge

line takes one to the summit. There are a couple

of points along the way that provide a good view of Mt. Hood, or

of a local boulder field.

We were frustrated at what we did not find along the

way. There was no snow. I had been

watching Mt. Hood for the last month

from the local hill that I visit on local walks, and had been

impressed by

what looked to be a good snow pack. Checking with

others revealed that the snow pack this year was lower than

normal, but was still heavy at higher

elevations. I made the unfortunate error of

assuming that there would be snow on Ghost

Ridge. But alas, we found the ground to be free

of snow, showing no more than minor dampness from recent

rains. We were depending on the snow for the water for

our camping. We studied north facing, shaded areas

that might have harbored a last remaining snow patch, but found

none. The heavy rains in Oregon last May

evidently removed the intermediate elevation snowpack.

John and I planned on camping in the trees just east of the Ghost

Ridge

summit. The lack of water compromised these

plans.

We only had a total of four liters of water for the two

days.

There were streams and lakes in the area, but it would have taken

several

hours of hiking to go there to fetch additional water.

Our final

solution was to eliminate the camping part of our

plan.

Instead we would put up the antenna, operate for a couple of

hours, cook

an early dinner, hike out to the car, and drive home in the

evening.

Field Day is often a compromise of one sort or another.

Shortly after arriving, we walked to the actual summit of the

ridge, perhaps 50 feet in elevation above the meadow

area. The photo below shows John with Mt. Hood

in the background. Mt. Jefferson could also be seen,

about 40 miles to the south.

Antennas in the Trees

Our antenna this year was a full wave loop, fed at the bottom

center. We took only an 8 foot piece of RG-58 coax

cable. 144 feet of #18 plastic insulated wire served

as the loop, transported on a piece of PVC.

Slots were cut in the 21 inch pipe to store the wire.

The loop was hoisted into a tree with a piece of brightly colored

Nylon

cord. The cord is wound on a piece of very

thin plywood

for transport, as shown below.

Also shown with the bright cord is a 4 oz lead

fishing weight (left over from the days when we used lead for such

things) plus a center insulator with coax connector to be used

with the closed loop antenna. The cord with the

plywood piece weighs 4.3 oz, which could easily be halved with a

rebuild.

Getting the antenna in the air begins with a tree

selection. Look for a tree with some open

branches that extend past the smaller ones near the tree

trunk. Try to avoid branches covered with

moss. Look for a fairly clear downward path from

the branch to the ground. After tying the weight to

the line, a large length of line is uncoiled onto the ground, well

away from the tree. The goal is to throw the

weight into the tree, over the selected branch, but to allow the

weight to keep going so it pulls the cord for some

distance. The branch selected this year was up by

about 40 feet. We probably had 60 feet of line

on the ground before the weight was thrown. I usually

grip the line about 18 inches from the weight and throw

underhand. John managed to get a great

photo of one of my throws, shown below.

(K7CVU photo.)

(K7CVU photo.)

The weight went over the branch, but then got stopped by another

branch. It did not stop and tangle because it

had been thrown without tension on the

line on the ground. Use of a heavy weight

helps the

process, pulling the line along as it falls. A

tempered tug or two on the line when it stops may help the

process, but don't get aggressive,

for this can cause the weight to circle a branch and

tangle. Once

this happens, there is no recourse short of climbing the tree or

cutting the

line. A lighter weight will work well with lighter

line, but

it then gets hard to see. A 1 oz weight works

well with

6 pound test mono film fishing line, but a reel is then required

to hold

the line. Bright paint on the weight is often useful.

Once we had the line in the tree, it was used to place the

insulated wire. No extra rope was

required. If we had been putting up a dipole, inverted

Vee, or an end fed wire, we might have attached a heavier rope to

the cord and used the cord to pull the rope into the

tree. The rope would then have been used to lift the

antenna.

Once we got the wire loop up in the tree, the ends were brought

together and attached to the center insulator shown in an earlier

photo. The loop was then tied out with lengths of

cord. This

loop antenna can be lifted into a tree without a heavier

rope. When we erect dipoles, we usually use 1/8 inch

diameter parachute cord to actually support the

antenna. An actual horizontal dipole is a very

rare antenna for me in the mountains. Instead,

an inverted Vee is used with one rope to support the antenna as

well as the feedline. The ends are then pulled out

with additional cord.

One vital rule applies to any of these

variations: Experiment with the variations at

home, if possible. As always, problems are often

avoided with experimental methods.

We got the loop up and installed after two or three

tries. (It never works right with the first

throw. Never!) The station was set

up, with an 8 ft piece of coax

attached directly to the loop. This was then attached

to a small

transmatch that uses screw driver adjusted mica compression

trimmers.

I've used this circuit (with its built-in bridge) for perhaps 20

trips to

the mountains; I keep coming back to it, for its the lightest

antenna tuner

I own.

More information was presented on how we get a wire into the trees

than

might normally be required. The reason is to

offer some

encouragement to a good friend who also went out for FD this

year.

He complained upon his return that “the tree ate my antenna.”

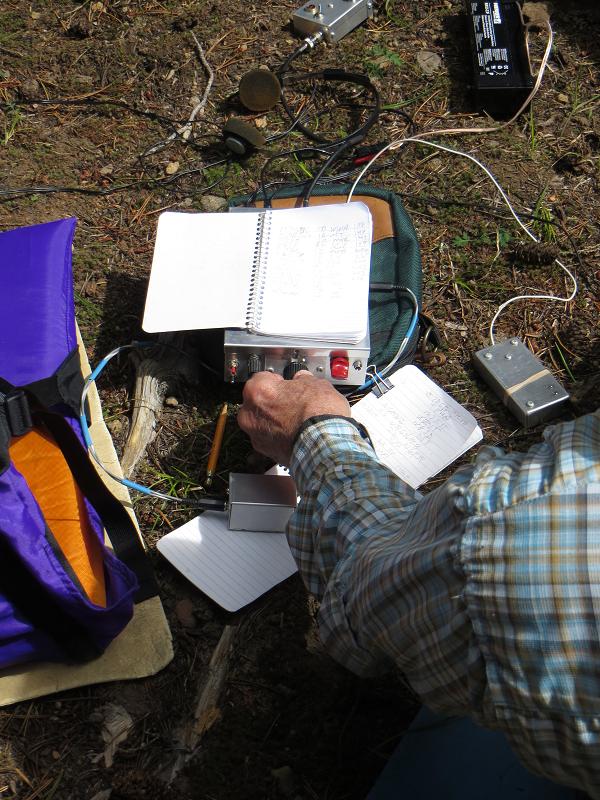

Our operating position is shown below. John is tuning

the band.

The “chair,” is a cloth and fiberglass structure that uses a

partially inflated air mattress as a pad. I

didn't find it all that comfortable. The power source,

a 2.3 AH, 12 volt sealed lead acid battery, is on the ground near

John's boot. A detailed shot of the station is

shown in the next photo. The transceiver is

built in a 2 x 5 x

7 inch box, which has a log book sitting on it.

The transceiver has two headphone outputs. A hand key

is to the right of the transceiver

while the paddle for the built in keyer is under John's arm in the

photo.

Propagation conditions seemed poor during this

contest. We operated the 40 meter CW band and

made only two dozen contacts. This seems to be about

the norm for our 1 W transceiver with a short afternoon operating

stint. I'm sure that this would have expanded

significantly if we had added Sunday morning

operations. Higher power is also a

possibility. There is always next year…

After taking the antenna down, we cooked a freeze dried

dinner. John had brought a new cooking tool, an MSR

Reactor Stove System. I was extremely

impressed. I've never seen a stove that was this

quick.

Hiking Companions

Earlier I alluded to an unusual experience on the approach

hike. It started at the trailhead parking

lot. John and I were donning our boots and

getting packs ready when a couple drove in and parked just down

the lot from us. They walked by to begin the

trail.

I said hello and started a conversation. Folks are

openly friendly

in the mountains, it seems. Something was said about

the Mazamas

and a name was mentioned. John recognized it, and it

soon became

clear that they had mutual acquaintances within the local hiking

and climbing

community. The gal then introduced themselves as Don

and Roberta

Lowe. I nearly fell out of my boots, for the

Lowes are

legendary for their books on the trails of Oregon, and later of

California

and Colorado. I have four of their Oregon books in my

library,

the first being “100 Oregon Hiking Trails,”

(Touchstone

Press, 1969.) The photo below shows

Roberta and Don

with me.

left-to-right: Wes, Roberta, Don. (K7CVU photo.)

left-to-right: Wes, Roberta, Don. (K7CVU photo.)

It was a tremendous pleasure to hike with them for a while.

The four of us hiked together until reaching the point where John

and I left the PCT to go up the hill.

Many thanks to John for the use of his photos.